Pierre G. Harmant's articles

From Camera to Cinemascope

Photography Was Born and Raised in France

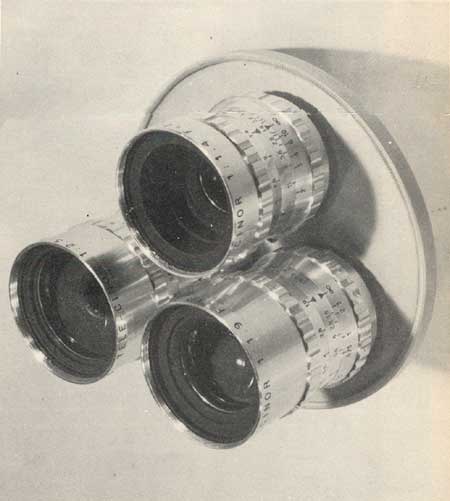

Shaping modern lenses in diamond grinders in SOM-Berthiot plant

Every time you take or look at a picture, every time you make or see a movie or watch TV, you can thank (or blame) the French for it. Primarily this is because Frenchmen invented and developed the first still-picture and the first motion-picture cameras, although they also took the first true photographs, created color pictures, made the first movie and the process now called Cinemascope.

In fact, while the Encyclopaedia Britannica notes, "photography was discovered by no one man," and while eminent Americans, British and Germans also have a variety of significant photographic breakthrough and achievements to their credit, there probably is no other science, art and industry in which Frenchmen have made so many basic and continuous contributions.

Authoritative Credit

In its list of "Great Inventions and Scientific Discoveries" the World Almanac gives first (1826) credit in photography to Frenchman Nicéphore Niépce, and secondary credits to Englishman Fox Talbot (in 1835) and to Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (in 1837). Niépce made the first true photograph with a camera obscura equipped with a lens. Fox Talbot and Daguerre established its use.

Nicéphore Niépce, inventor of photography. Photo-Hachette

The Inventor

Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) was born at Chalon-sur-Saône and retired to the country after the Revolution due to ill health. He spent his life in research, and from 1813 to 1817 occupied himself in trying to find stones that could be utilized in the lithographic process. In a letter in 1816 to his brother Claude, he reported that he had succeeded in producing a negative image by using silver chloride on paper, but had been unable to "fix" it. The result was more successful in 1822 when he used asphaltum.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica dates true photography from that date, when it declares, "the first permanent photograph was made that year by Niépce." (The process, however, was called "heliography.") By 1826, the method was perfected and bituminous tin plate was sent to Parisian engraver Frédéric Lemaître (1797-1870) to be engraved and printed on paper.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre established use of camera. Photo-Hachette

The Developer

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1789-1851) was born at Cormeilles-en-Parisis near Paris, and became an artist and scene painter. (His illusionistic Diorama, a popular spectacle hall where optical illusion and lighting effects combined to cast huge pictures with an illusion of depth, was a Paris landmark long before his name was connected with photography.) In 1826, hearing of Niépce's work through their common supplier of optical equipment, Charles Chevalier (1804-1859), an important innovator of the period, Daguerre approached the researcher through letters and asked to work with him toward an eventual partnership. Niépce, due to financial embarrassment and discouragement at the lack of interest in his innovations in scientific circles, agreed in 1829 to sign a contract of association.

After Niépce's death, Daguerre in 1835 discovered accidentally that if an iodized silver plate were exposed in a dark room and then fumed with mercury vapor, a clear, direct, positive image would result. This "daguerreotype" process was the first successful photographic method to be made public. It was introduced as a "gift to France and the world" in 1839, by the Academy of Sciences and the Beaux Arts after being bought by the enthusiastic French government. (It gave him and his descendants a perpetual award.) Parisian painter Paul Delaroche went so far as to say, "the daguerreotype process completely satisfies art's every need."

By 1840, Hippolyte-Louis Fizeau (1819-1896), had perfected the process further by working it through a silvered copper plate fumed with iodine and resensitized with a bromine water bath before exposure. This increased the plate's sensitivity by fifteen times.

Photoengraving and Allied Innovations

Dr. Albert Donné (1801-1877) was the first (in 1839) to show proofs of etched daguerreotypes. Hippolyte-Louis Fizeau and Antoine-François-Jean Claudet also etched them, and Alphonse Poitevin (1819-1882) turned out relief electrotype printing plates from chromated gelatin originals. Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887), an amateur chemical researcher, discovered in less than sixteen days in 1839 a process which allowed him to achieve direct positive images on paper which were practically perfect. An hour's posing time was necessary, plus the use of paper coated with silver chloride, darkened by exposure to the light, then impregnated with potassium.

Other Original Contributors

The rise of the bourgeoisie after the French Revolution created a new demand for pictures and gave impetus to discoveries in the light-sensitive properties of silver salts in the recording of camera images. It was in 1798, that Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin discovered the light-sensitiveness of silver chromate. Great improvements in this area were made in 1848 by Edmond Becquerel son of famed physicist Antoine Becquerel and father of future Nobel Prize Winner Henri Becquerel. In collaboration with Claude-Félix-Abel Niépce de Saint-Victor (1805-1870), a pioneer in the art of printing on glass, Becquerel observed that silver chloride first darkened by exposure could record the spectrum of the sun by direct action, in colors approximately similar to the spectrum itself. The colors, however, could not be "fixed.".

In 1847, Louis-Désiré Blanquart-Evrard (1802-1872) used albumen to keep the sensitive silver salts more on the surface in printing film. He thus obtained negatives which permitted the multiplication of proofs. The same year, Romieu suggested that a mixture of alkaline bromides and chlorides containing gelatin for salting be floated on silver nitrate solution . In 1850 Gustave Le Gray improved color by using a gold salt.

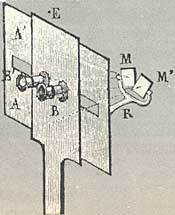

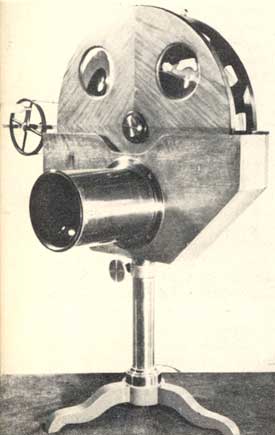

Duboscq's stereoscope, as presented in 1852

The stereoscope, soon to become immensely popular all over the world, was invented by Jules Duboscq (1817-1886), and presented originally at the London Universal Exhibition in 1851. Millions of people enjoyed the impression of dimension and space through the two images utilized in Duboscq's gadget.

In 1851, Henri-Victor Regnault (1810-1878) discovered pyrogallol, which permitted the "physical development" of film in a much briefer period than hitherto.

In further improvements, Marc-Antoine Gaudin (1804-1880) suggested in 1853 that all the ingredients necessary for impression by light could be incorporated within collodion. He also predicted modern photography by saying that the better improvement would be a light, sensitive collodion coated directly on plates. Humbert de Molard in 1855 recommended that a precipitation of silver chloride, washed and suspended in a solution of gelatin or starch, be painted on paper. This came to displace albuminized paper. In 1877 Alfred Chardon ushered in modern photography by proposing an emulsion of dry collodion, not requiring preservatives,.

Alphonse Poitevin introduced chromium salts into photography in 1855. His method formed the base of what is called the "carbon" process. The research for this process was stimulated by a contest organized by the Duke of Luynes, aimed at discovering a process for producing absolutely unalterable photographs. The prize was shared in 1859 between Testud de Beauregard, Garnier and André Salmon. Poitevin received a medal, Garnier and Salmon are also the initiators of the powdering process. The "gum" process was proposed in 1889 by Victor Artigue and the first half-tone prints were presented in 1884 by Robert Demachy who perfected printing with gum in 1894.

The Camera

Making possible the Niépce and Daguerre cameras, Charles Chevalier in 1821 combined a positive lens of crown glass with a negative lens of flint glass. Previously, there had been chromatic aberrations in lenses, and the Chevalier lens corrected this. In 1825 he also invented a prism, shaped like a triangle and with plane and curved faces, which replaced camera lenses and mirrors.

The first exposure meters for daguerreotype were constructed by Jean-Baptiste Soleil in 1843. Other opticians of note were Lerebours, who invented a three-component lens in 1846; Derogy, who invented a "multiple focus" lens in 1858 (actually a set of parts which could be assembled in various combinations depending on the particular shot desired); and Jamin who devised lenses with movable components. At the turn of the nineteenth century the Parra-Mantois Company was turning out high quality glass which led to France's conquest of the world optical market. This firm still functions today, along with such other leading French lens manufacturers as Etablissements P. Angénieux, Etablissements Benoist-Berthiot, A. Lévy Boyer, Fleury-Hermagis, Foca, Kinoptik, Lacour-Berthiot, and Société d'Optique et de Mécanique de Haute Précision (SOM-Berthiot).

The first commercially-available cameras for photography were made (for Daguerre) in 1839, by Alphonse Giroux, a Paris bookseller. They were wooden boxes, sliding inside other wooden boxes for focusing, and had Chevalier simple achromatic lenses, metal shutters, ground glass backs and holders for the plates. (The first cameras, incidentally, weighed about 121 pounds, and efforts were soon underway to reduce their weight.)

First use of a tripod under a camera was by Baron P. A. Séguier in 1839. He also introduced the collapsible bellows to make the cameras more portable.

Chevalier built the first "junior-sized" camera, called the "photographe."

The double drop shutter was invented in 1892 by Decaux and a precise focal plane shutter by Albert Londe and Dessoudeix in 1885. About 1860 Relandin and Humbert de Molard conceived roller blind shutters, and in 1893 Vicomte Ponton d'Amécourt devised a shutter with an adjustable lightslit.

The spectroheliograph, a necessity in spectral photography, was independently created in 1890 by Frenchman Henri-Alexandre Deslandres and Englishman G. E. Hale.

From Daguerre to Cartier-Bresson

French Photographers of Distinction

Daguerre may well be called the world's first professional photographer, and following in his tradition, there have been a multitude of Frenchmen who have earned distinction in scientific, artistic and news photography.

As early as 1845, Jean-Bernard-Léon Foucault (1819-1868) and Hippolyte Fizeau took "daguerreotypes" of the sun. Foucault discovered and August Toepler applied the "Schlieren" method, which is based on slight differences of refractive index in the air, for instantaneous photographs. By this brilliant development, it was thereafter possible to photograph sound waves accompanying projectiles in flight, convective streams from heated bodies, vortex rings gathered in warm air, or vapors of various densities.

The first illustrated book appeared in 1849--a book of daguerreotypes of the remarkable monuments of the globe. This was thanks to the genius of Fizeau who in 1841 proposed a method of engraving which could be used to reproduce daguerreotypes. Other photographic volumes of the time included the voyage of Maxime du Camp in the Orient, Egypt and Nubia (1840)--with true positives drawn from negatives on paper on the spot--and "Views of Jersey" (1853) photographed by Charles and François Hugo and Auguste Vacquerie, to illustrate the verses of Victor Hugo.

It was in 1850 that Gustave Le Gray sent eight of his photographs to an art exhibit in Paris. The art jury accepted them and catalogued [sic] them as lithographs. When it became known that they were photographs, however, they were removed from the exhibition. Le Gray probably was the first to make one print from several different negatives--for instance, to put clouds over seascapes.

Photogrammetry

In 1852, Aimé Laussedat (1819-1907) was the first man to compile map data based on measurements from photographs. He thus is called the "father of photogrammetry" which is picture measuring, and particularly used today in making maps from aerial photos. Laussedat had a far-seeing conception of the possibilities of photogrammetry, and if he were alive today no doubt would be impatient to have a camera on a sputnik. About 1859 he constructed the first phototheodolite (topographical apparatus), which was used to make a map of Grenoble in 1864. Meanwhile the new science of photogrammetry was advanced by Félix Tournachon (called Nadar) who in 1858 took the first photos from a balloon. Paul Desmarets in 1880 introduced dry plates to aerial photography, and took instantaneous pictures over Rouen in 1885. That same year, Gaston Tissandier took aerial photos of Paris. Later, a member of the French Academy of Sciences, Georges-Jean Poivilliers, invented an apparatus to plot aerial images, thus facilitating cartographic work.

The first man ever to take pictures from an airplane was Louis Meurisse (in 1909).

In this day of missiles and sputniks, it is particularly astonishing to record that way back in 1888 Amédée Denise created an automatic apparatus capable of taking a dozen simultaneous pictures at the summit of the trajectory of a rocket!

By mid-nineteenth century, photography had so taken the public fancy and aroused such scientific interest that the Société Française de Photographie was organized in Paris in 1854.

Photographic Pioneers

The Kodak-Pathé plant at Vincennes

In 1860, sculptor François Willème (1830-1930) patented his photoplastic process which allowed accurate reproductions of the head and shoulders after 24 images had been taken all around the subject. (This was a photographic application inspired by G. L. Chrestien's invention of the "physionotrace" in 1785.

Another Parisian sculptor named Adam Salomon was the original user of a strong side light to give the so-called "Rembrandt effect" to his photographic portraits. Moreover, he was the first master retoucher. In 1868, in fact, the Edinburgh Photographic Society took a hard look at some of Salomon's prints to see whether they were "pure photographs or indebted to retouching for their beauty." (They had been retouched.)

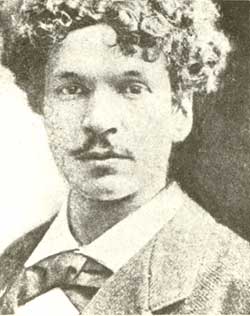

Louis Ducos du Hauron paved way for modern three-color photography. "Cinémathèque Française"

Charles Cros

Louis Ducos du Hauron (1837-1920) published in 1869 a book setting forth the principles which provide the bases for all modern processes (both additive and subtractive) of three-color photography. He and Charles Cros (1842-1888) also made apparatuses for viewing three pictures directly rather than by projection. The standard histories in the field give du Hauron full credit for the first description of the subtractive systems which are now the most important practical color photography methods in still and motion pictures.

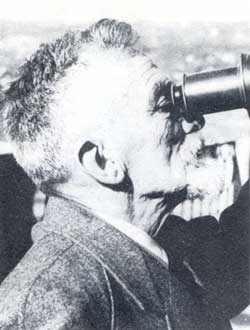

It was some time after the middle of the nineteenth century that Etienne Jules Marey (1830-1904) first took photos of projectiles in motion. In 1882 he made a "photographic rifle," which took a dozen pictures a second on a revolving plate. A perfection of this, using film, in 1890 made Marey the inventor of the photochronograph, which was the first practical apparatus allowing the taking of a series of images.

Libessart and Séguin studied sonic and supersonic waves with the stroborama. Tenot and Valensi trained their cameras on the phenomenon of cavitation, which led to the development of aerodynamics.

The first radiographic images were obtained by Rou and Balthazard in 1897. Slow movement speeds were studied by Comandon, who produced a movie showing the circulation of sap and blood. Charles Metain gave up professional photography to concentrate on biological cinematography, and R. Moricard and Pédebidou made films on cytology.

In 1908, in Lyons, Alphonse Bertillon (1853-1914) created the science of criminal identification through photography, still in wold-wide use today.

A unique part was played in the invention of color photography by Gabriel Lippmann (1845-1921). In 1891 he demonstrated the phenomenon of stationary waves for the reproduction of colors. This "interference" principle gave images of an astonishing quality. In 1908 he was given the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Edouard Belin, born in 1876 and still active today, is the pioneer in telephotography. In 1907 he made the first transmission on a closed circuit (Paris-Lyons-Bordeaux-Paris), and in 1921 scored the first successful trans-atlantic transmission (Malmaison-Annapolis) by teletype.

Jules Janssen used daguerreotype plates to register the passage of Venus across the sun in 1874. Léon Gaumont was the first to record (in 1912) an eclipse of the sun in color. In 1932 Leclerc and Budry filmed a sunrise on the moon from the Paris Observatory. A much faster method of photographing nebular formation for meteorological research was developed by Joseph Devaux in 1933.

Bernard Lyot of the Paris Observatory succeeded for the first time in 1931 in photographing the solar corona outside eclipse, and in 1936 photographed the inner corona. For this accomplishment, he used a remarkable telescope he had designed himself, called the "coronagraph." By 1941, with improvements in his apparatus, he not only obtained pictures of the corona, but also direct photographs of the chromosphere, prominences and sunspots, that were equal to or better in quality than those taken with the spectroheliograph.

One of the ablest contemporary photographers, often called the very best, is Henri Cartier-Bresson. His work has been featured in Life and in other great picture magazines of the world.

It should be noted also that Europe's top record of progressive work in the field of modern photography is the annual Photographie, published by Arts et Métiers Graphiques in Paris.

For the World's Billions

French Movie Firsts

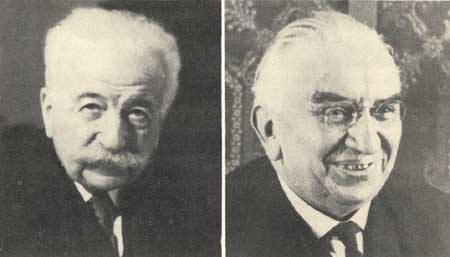

Auguste and Louis Lumière, inventors of the movie camera, three-color screen photography, and first movie producers. Photo Blanc & Demilly

In the creation and development of today's universal medium of entertainment and education--the motion picture, France certainly occupies a leading place.

The motion picture camera was invented by Auguste (1862-1955) and Louis (1864-1948) Lumière. Photographic manufacturers at Lyons, the brothers patented their "cinematograph" in 1895 in Paris. This apparatus was a combination (by adjustment) camera, film-printer and projector. It was mobile, could clearly record the outside world, and reduced the rate of exposure from Edison's 48 images a second to 16, the actual standard of silent movies today. Using the cinematograph, a public show was opened at the end of the same year in the basement of the Café de Paris. The first public cinema, it prospered from the start.

The World Almanac's list of "Great Inventions and Scientific Discoveries" gives the sole credit for the creation of three-color screen photography to Louis Lumière in 1904. The Lumière "Autochrome," marketed in 1907, was the first commercially successful color process. It utilized a modification of an additive process originally suggested by du Hauron.

First Movie

The Lumière brothers also made the very first motion picture, titled "L'Arroseur Arrosé" (literally, "The Sprayer Sprayed"). It was a slap-stick sequence in which a man steps on a hose to interrupt the water-flow to another man sprinkling his garden. The latter of course looks into the hose nozzle to see what is wrong, the mischief-maker lifts his foot from the hose, and the gardener's face is sprayed with water. Decades later this was still good for a laugh in many a movie comedy.

The Lumières went on to send photographers around the world to take moving pictures of far-away places and peoples and bring back film recordings for European and American screens.

Movie Pioneers

Duboscq's early projector. Photo "Cinémathèque Française"

Even before the Lumières, other Frenchmen contributed significantly toward the evolution of the motion picture. Thus, the Encyclopaedia Britannica declares, "A complete anticipation of the motion picture was embodied in a patent application by Louis Ducos du Hauron, in France, filed April 25, 1864.

Then, there was Emile Reynaud (1803-1880), who developed the "praxinoscope." This involved colored manual designs representing the phase of a movement and their synthesis by projection. Reynaud thus was the creator, as well, of animated drawings. This type of "optical theater" was extremely successful and was the forerunner of modern projection. (It might be noted that Reynaud ran his films by using perforations in their margins--an invention attributed to Edison.)

Mention should be made, furthermore, of Jean-Louis Meissonier, the French painter. He became involved in disputes with the academicians over the posture of horses in his pictures and heard that Leland Stanford, the California railroad tycoon, was in Paris with pictures providing photographic records of horses in fast motion. These pictures proved Meissonier's horse postures were correct. At his request, furthermore, the machine that had made the pictures was brought to Paris and Meissonier synthesized them into "motion pictures" by projecting transparencies on a machine.

After the practical and commercial launching of the motion picture by the Lumières, the world's first newsreels were made around 1900 by Charles Pathé in his studio at Vincennes. Surgical cinematography was begun in 1900, by Professor Louis Doyen.

Georges Méliès. Photo "Cinémathèque Française"

It was just before the turn of the century (in 1896) that the great Georges Méliès first began to make his impact on the future of motion pictures. A magician appearing in a Paris theater, he took film of magic tricks and, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, "gave the motion picture new life." He was the first to introduce fade-outs, dissolves and double-exposures to the art of the film.

In his authoritative study, The Rise of the American Film (Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1939), Lewis Jacobs says: "It is with a Frenchman, Georges Méliès, that the American film as an art begins." He "started movies on a new course, broadened their scope and forced attention on their creative possibilities." He was the movies' "first great craftsman and the father of their theatrical tradition." At other points in his broad-scale history of the American movie, Jacobs states: "The first cameraman in the world to show individuality of technique was Georges Méliès of France. His films, particularly those from 1900 on, pointed the way for a creative technique and led to the discovery of film dramatization, which was to change the whole course of moviemaking." Finally, Méliès was "the dean of movie directors, the pioneer of film organization, the first movie artist, and discoverer of the camera's unique resources," says Jacobs. Although Méliès made over 450 movies, some of them in color, in the tradition of many of the movie greats, he died franc-less, in 1938, at age 77.

A world-known manufacturer of film equipment today is André Debrie.

Impact of French Film in the U.S.

Charles Pathé, first newsreel producer

In a speech last fall to the American Club in Paris, Cecil B. DeMille says "The French four-reel film Queen Elizabeth, starring Sarah Bernhardt, brought to America in 1912 by Adolph Zukor, created a new audience for motion pictures in the U.S." This picture showed that people would go to see feature-length pictures. According to Lewis Jacobs, "French films like Queen Elizabeth, Camille and Madame Sans Gêne in their length and power of conception dwarfed contemporary American productions."

Commenting on later French contributions to the American screen and movie technique, Jacobs says: "France, having sent to America an occasional imposing film such as J'Accuse (1921), a spectacular fourteen-reel story of the early days of the World War, directed by Abel Gance, suddenly in the late Twenties presented important innovations to the motion picture world. Unusual cinematic sensitivity was displayed in The Passion of Joan of Arc, directed by Carl Dreyer and distributed in the U.S. in 1929, in Thérèse Raquin and Les Nouveaux Messieurs, by Jacques Feyder, which was little shown in the U.S. and in The Italian Straw Hat, by René Clair. These films were unlike any that had yet appeared..."

Henri Chrétien, inventor of "Cinemascope". Photo Twentieth Century Fox

It was in 1926 that a Frenchman created what is now called "Cinemascope." Henri Chrétien that year patented his double-lens, panoramic, color process called "Hypergonar;" In 1937 he demonstrated it on a 6,500-square-foot screen at the Paris World Fair, and sold it in 1952 to Twentieth Century-Fox.

Latest Movie Contributions

In 1928, the Eastman-Kodak Co, made the "Kodacolor" process commercially available for amateur color movie photography. This in fact is the "lenticular" film process, patented by Rodolphe Berthon in 1908, and later perfected by Georges Keller-Dorian.

The French have made notable contributions to the development and use of films in science and medicine, and use of films in science and medicine, and in education. some of the outstanding innovators in the educational picture filed are Marc Cantegrel (technical instructive films), Jean Brérault (primary teaching), Maxime Prudhommeau (psychological research), and Jean Painlevé (science research and instruction).

Millions in the world, of course, are now aware of the underwater picture-making genius of Yves Cousteau.

Artists of World Renown

Among the great French actors and actresses who have made their large impact on the cinema are Sarah Bernhardt, Harry Baur, Charles Boyer, Maurice Chevalier, Claudette Colbert, Danielle Darrieux, Fernandel, Jean Gabin, Louis Jouvet, Max Linder, Michelle Morgan, and Raimu.

Among top movie directors produced by the French cinema industry in recent decades are Claude Autant-Larat, Benoit-Lévy, Marcel Carné, André Cayatte, René Clair, René Clément, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Julien Duvivier, Anatole Litvak, and Jean Renoir.

Contemporary Creativeness

French Photography Stays Ahead

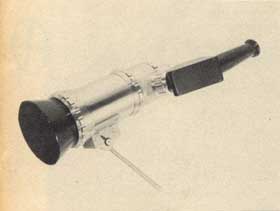

SOM-Berthiot's telescopic lens. Photo Cabriel

Present-day indications that the French are still in the forefront of creation in the general field of photography:

- The more than 150 French firms manufacturing film, camera, optical instruments and related items, now turn out products sold in some 30 countries in the world.

SOM-Berthiot's glass-polishing...

metal parts being protected against corrosion

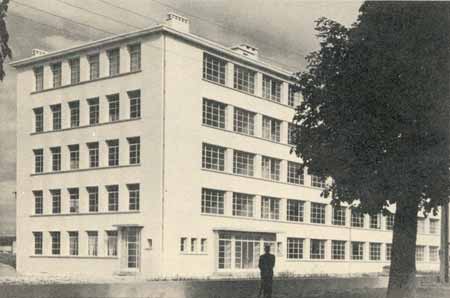

- France is the top supplier of glasses for optical purposes--the nation's producers providing over 75 percent of all those used in the world. (The Société d'Optique et de Mécanique de Haute Précision this year celebrates its hundredth anniversary with the opening of a new, highly-modern optical equipment plant in Dijon.)

The new SOM-Berthiot factory in Dijon

- The revolutionary, lightweight, portable TV camera (used by CBS News in the United States), was developed by the Compagnie Générale de Télégraphie Sans Fil.

- The world's first 8 mm movie camera with an automatically adjusting diaphragm was created in 1956 by the Société Leveque.

- Schools of all categories in France are equipped for cinema, and thousands of educational and documentary films a year are state-financed and distributed free.

SOM-Berthiot's latest cine turret. Multi Photo